Safety Charge: How the FIA is leading the way in high voltage racing

As electric and hybrid racing becomes more prevalent Safety Week 2026 revealed how the FIA is using the lessons learned at the top levels of motor sport to build tools for every level of competition

Back in 2009 the sight of mechanics in Formula 1 garages donning protective clothing and establishing safe zones around cars equipped with Kinetic Energy Systems (KERS) seemed like a thrilling glimpse into the future of racing – albeit one that appeared to come with some potential hazards.

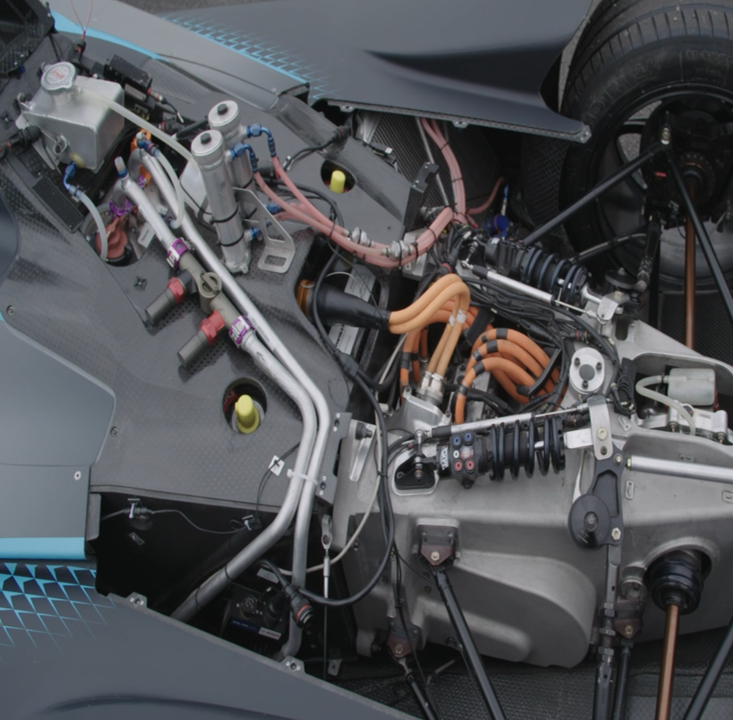

Fast forward almost two decades and that future has not just arrived, it’s commonplace. From the flagship electric ABB FIA Formula E World Championship to enormously powerful hybrid technologies in Formula 1 and the FIA World Endurance Championship, high voltage racing isn’t just a descriptor of the action on track, it’s a way of life.

The reality of that energy transition in motor sport has led to an ever-evolving safety ecosystem around the use of high voltage in racing environments. And on day three of FIA Safety Week 2026, the Federation’s e-safety experts explained how procedures honed at the top level are being brought to other categories. And the starting point, according to FIA New Energies Safety Manager Yvan Devigne, is creating a defined organisation to deal with safety protocols and incidents.

“We need to clarify what are the roles and responsibilities of each and every one, make sure we have procedures in place and associated equipment on the right persons,” Devigne explained

That structure is built around three operational pillars: the FIA e-safety delegate on-site, a dedicated race control coordination link, and a technical ‘system expert’ to provide rapid initial assessment—potentially using post-incident telemetry—to identify whether a car is safe.

“Then, on the organiser circuit side, it’s the marshals,” he added. “They must understand the technology and the risks associated with it. They must be able to identify whether the risk is present or not and understand how to behave in specific situations. It’s the same on the rescue and medical side. They will work and lean on the car to rescue the driver, so they need proper training.”

The process begins with an e-learning module. “It’s here that we give an introduction to e-safety to people from ASNs and circuits so they can do it at home,” said Devigne. “Then when we reach the race week, people are on-site, especially the e-safety delegate, and we can organise briefings so we can go again through the same content, give more specific details into procedures, and also hold interactive sessions”.

Top tier lessons: learning from major championships

And the procedures followed are developed and refined at the top levels of FIA competition as FIA e-Safety Delegate Josef Halter explained, using the FIA World Endurance Championship’s 2025 season as an example.

In Bahrain, an unusual ‘red light’ incident in the pit lane when a driver didn’t correctly complete a switch-off procedure caused distraction among teams and organisers. “All of a sudden [everyone is] focusing on this car and not focusing on the race and/or the session anymore,” Halter said, underlining why disciplined briefings matter.

In Austin, wet conditions added complexity when a car lost isolation and displayed a red light. Even after the vehicle’s safety systems opened the battery contactors and the car returned “from red back to green,” the Race Control deployed the e-safety delegate for verification. The takeaway for Halter was that while wet conditions bring additional challenges, “they do not mitigate our high voltage procedures.”. A further improvement followed—adding a shelter to quarantine areas so teams can work “under a cleaner and drier environment.”

Finally, in São Paulo, an isolation drop occurred “right before the pit entry,” resulting in a red car entering the pit lane unexpectedly. To standardise fast, clear communication of issues, the FIA uses a scenario-based system in which a team simply has to message scenario 1-4 to inform race control of the status. However, the incident in São Paulo existed outside the scenarios and led to the eventual creation of a safe ‘parking’ zone at or near the pit lane entry.

Guiding force: best practice at every level

The FIA is now packaging this experience into tools that can be adopted beyond global championships. Devigne described the intent behind the newly published FIA e-Safety Guidelines.

“It’s not a regulatory document, it’s really to explain where we come from on every single point… to enable ASN organiser to replicate what we do and to see how they can adapt that to their environment.” Alongside the guidelines, the FIA is providing an e-safety toolkit—briefings, handouts, and operational documents—available for adaptation.

The result is a safety programme designed not just for the major FIA championships, but for competition at every level – and as hybrid and electric cars become common in national and grassroots series that expertise is critical.

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter