FIA Insights: Staying ahead of the curve – Why the FIA is stiffening the tests around wing flexibility

From this weekend in Barcelona, the FIA will impose tougher tests on front wings to match the tightening of tests on rear wings imposed in China and Japan. FIA Single Seater Director Nikolas Tombazis explains why the changes have been made and what they mean going forward.

At this weekend’s Spanish Grand Prix, the FIA is introducing a further tightening of the load tests applied to the wings of F1 cars in a bid to address concerns around flexibility and the performance benefits teams might gain through the use of wings that flex under load.

Ahead of the 2025 season, the Federation announced that in response to concerns expressed throughout the 2024 campaign that some teams were pursuing designs that might reducing drag at high speed or even change the aerodynamic balance of the car from low-speed to high-speed, it would “introduce either new or more challenging load-deflection tests for the front wing (from Race 9, Spanish Grand Prix), the upper rear wing, and the beam rear wing”.

As FIA Single Seater Nikolas Tombazis explains: “When championship battles become intense, teams tend to focus on each other’s cars a lot, and naturally they raise concerns and over the latter half of the season we came to the conclusion that we needed to toughen a bit more the tests for 2025.”

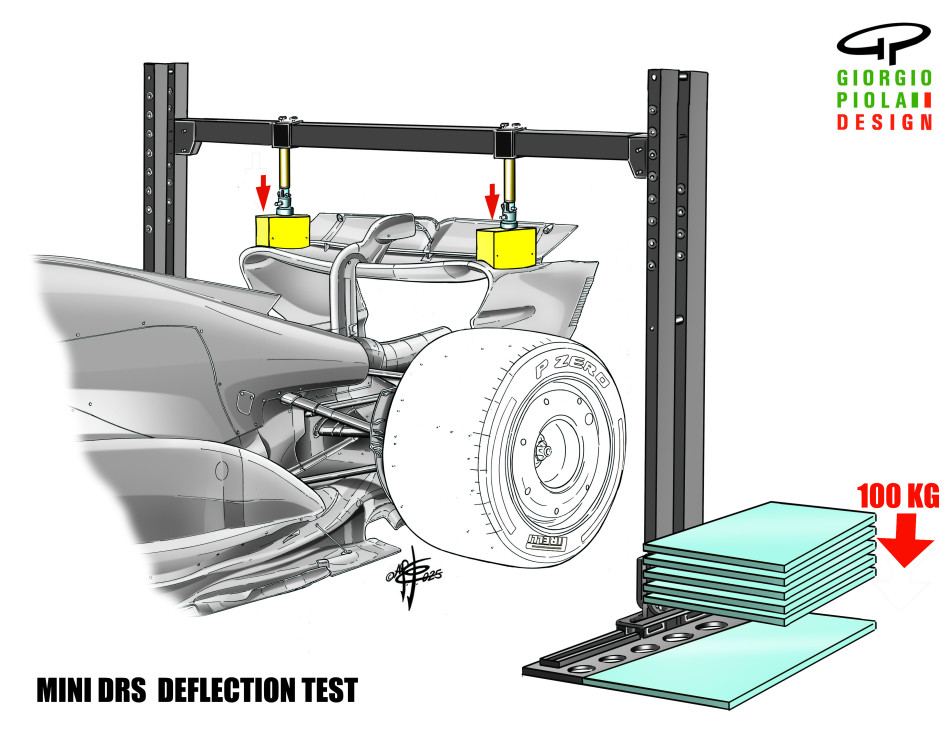

Rear wing deformation was initially addressed by the 2025 regulations, in which Article 3.15.17 specified that if 75Kg of vertical load were to be applied on either extremity of the rear wing mainplane, the distance between the mainplane and the flap (also known as ‘slot gap’) should not vary by more than 2mm.

“The 2025 regulations were designed to counteract the so-called ‘mini-drs effect’ that became quite a talking point in the autumn of last year,” says Tombazis of concerns that rear wings were flexing to the degree that under load a drag reducing gap was appearing between rear wing elements. “That test was applied from the start of the season, but it soon became apparent it was insufficient.”

In a bid to monitor the success of the regulation, cameras were mounted on cars during free practice sessions at the season-opening Australian Grand Prix and having analysed the footage the FIA concluded that even tougher tests were needed. At the Chinese Grand Prix, the tolerance was reduced to 0.75mm and at the following race, in Japan, to 0.5mm.

With rear wing flexing addressed, attention now turns to front wings. But why only from this weekend?

“Over a sequence of races at and following the Belgian Grand Prix we installed cameras on the front wings of all cars and again we concluded that the tests would need to be toughened,” says Tombazis. “That conclusion was arrived at quite late in the year, however, and we felt that if we had introduced extra tests at the start of this season, it would have been tough on teams and may have led to existing front wings being scrapped, and extra expense. Therefore, we felt that deferred introduction was more sensible.”

The parameters of the tighter tests are defined in revisions to Article 3.15.4 and 3.15.5 of the 2025 Technical Regulations, which respectively govern Front Wing Bodywork Flexibility and Front Wing Flap Flexibility.

The former originally stated that when 100kg of load is applied symmetrically to both sides of the car the vertical deflection must be no more than 15mm and when the load is applied to only one side of the car the vertical deflection must be no more than 20mm.

However, from this weekend on, when the load is applied symmetrically to both sides of the car the vertical deflection must be no more than 10mm and applied to only one side of the car the vertical deflection must be no more than 15mm.

Regarding Front Wing Flap Flexibility, the regulations stated that “any part of the trailing edge of any front wing flap may deflect no more than 5mm, when measured along the loading axis, when a 6kg point load is applied normal to the flap”. From this weekend the amount of permitted deflection drops to just 3mm.

While the reductions may sound small, the increase in rigidity is significant and according to Tombazis will hopefully draw a line under the issue for the remainder of the year.

“Obviously it is fair for the FIA to add more flexibility tests or stiffness tests when it judges that a certain area may be getting exploited a bit too much, but yes, we hope it will be the last time we’ll do anything for this year.”

To ensure that is the case, testing of components takes place on a regular basis.

“We check the teams at various points across the season and we ask them to bring certain components along and we’ll check them in isolation and sometimes test them on the whole car,” Tombazis explains. “We frequently test in parc fermé conditions—either on Saturday after qualifying or Sunday morning, as obviously, in parc fermé teams cannot make changes to their car. That ensures that they’re not fitting a stiff wing for the test and running something else in the race. We also occasionally conduct checks after a race if we feel there is a reason to do so. Those tests would be static load tests, as defined in Article 3.15 of the Technical Regulations.”

With a new set of regulations coming into force in 2026 it is expected that there will be fewer issues with the flexibility of components, though Tombazis says that in a sport fuelled by engineering ingenuity the FIA will continue to test areas of concern.

“There are areas where the propensity to have flexible components is less pronounced, because of the straight-line mode, for example and therefore in some areas it may be that at some point we choose to ease the toughness of the tests,” he says. “But fundamentally the philosophy is the same. We need to be vigilant, and we need to keep testing. In fact, we are defining the loads for next year now. So, we will see how the first evolves and if we need to react to maintain fairness, then we will do so.”

Illustrations credit: Giorgio Piola Design

Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter